Why we should talk about the "angry women" in fiction — Feminine Rage #2

angry women are not angry, just tired.

This is Part Deux of a two-part series about female rage. If you haven't already, check out Part 1, a review of Siobhan MacGowan's book The Trial of Lotta Rae!

Siobhan MacGowan’s debut novel The Trial of Lotta Rae is set at the turn of the 20th century, a pivotal period in history for women’s rights. She dissects, in beautifully-articulated detail, the complex intermeshing of assault, sexuality, justice, and the systemic oppression of women as a whole. But one facet stood out to me in particular, and that is how the victim Lotta Rae’s anger is portrayed.

At first pass, Lotta is your typical angry female character. Wronged as a child, she grows up to be a defiant and vengeful woman with murder on her mind. At times, her anger is dormant, bubbling under the surface, and at others, explosive and confusing. She becomes the definition of ‘feminine rage’ — a term referring to the anger or fury experienced by women in response to societal injustices and gender-based discrimination.

Feminine rage in fiction is not a new concept. We see examples of it in characters like Medea, who flips her shit after being cheated on, and Mina Harker from Dracula, as well as in contemporary literature: Offred from The Handmaid's Tale, Katniss Everdeen from The Hunger Games, and Marvel heroine Scarlet Witch/Wanda Maximoff.

These women represent the frustration of women who are oppressed by patriarchal power structures, and as feminism exponentially gained traction in recent years, we have come to realise that their specific strain of anger is a completely valid emotional response to oppression. Many of us look to them as inspiring icons to emulate.

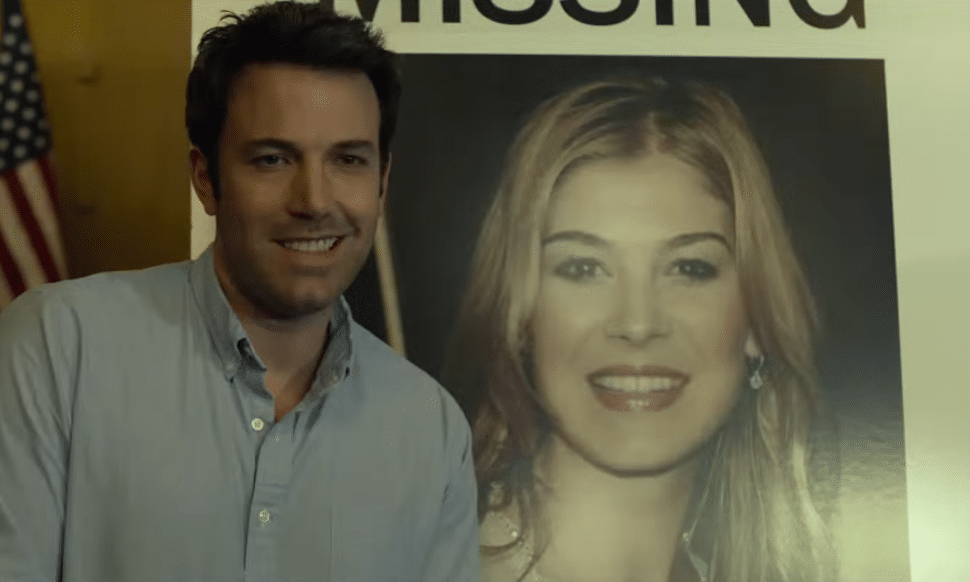

But why do we not spare the same understanding towards other rageful female characters like Medusa from Greek mythology, Amy Dunne from Gone Girl, or even Ursula from The Little Mermaid?

Virginia Woolf once said she hoped women would soon develop a literary style of their own, shaped “out of their own needs for their own uses”. In that vein, what, then, differentiates the narratives of Katniss Everdeen and Amy Dunne, if both are moulded from the female experience?

1. Because angry women are crazy

Characters like Amy are portrayed as villains because women who express anger in a way that is considered abnormal or illogical are deemed irrational and volatile. And so these villains, spurned and offended (by men), turn to lying, manipulation, or straight-up murder as a means to purge their emotions.

As a result, they are immediately outcasted as the Big Baddie to be defeated. Hell, even heroes like Wanda and Katniss aren’t free of moments when their sanity and validity are called into question, just because they had the audacity to display feelings of grief or anger.

So, if a woman’s display of anger is a testimonial to her villainy, why does the same not apply to men?

It is not that we have collectively understood Amy Dunne or Medusa’s stories incorrectly — I’m not saying we should start faking our deaths to punish our cheating partners, or killing men and burying them in cement — but that perhaps we have a tendency to conflate ‘reasons’ and ‘excuses’.

Real life is not perfect, and while feminine rage is often a response to real and justified grievances, it can manifest into negative outputs just as much as it can be positive. Is it necessarily desirable, for the good of society? No. But is it completely and understandably human? Yes.

2. Because angry women are ugly, inside and out

The angry woman in question is usually also portrayed as fat, ugly, or hag-like. Or a witch. Or, if she’s beautiful, she is also not running on a full set of wheels (i.e. utterly off her rockers), which moots any validity she has as a person.

This idea that angry women are unattractive or undesirable is rooted in very specifically-male ideas on how women should behave and present themselves. Yet, we cannot help but identify aspects of our womanhood in these characters.

Like Amy Dunne, we often bear the emotional and physical burdens in the household and within romantic relationships (the ‘mental load’). Like Offred and Medusa, we find ourselves at the mercy of men who think they can do whatever they wish to us. Like Lotta Rae and the countless silenced women she represents, we have been failed by a system that was built by men for men.

Retaliation to these unspoken biases would render us women petty, overbearing, paranoid, and difficult. It is unbecoming. Unladylike. So, we are made to turn the other cheek, be the bigger person, ignore him, he’s just a douchebag! But does this really make us the bigger person? Or does it only further diminish our emotions and lived experiences?

These ‘villains’ have done what many of us are sometimes afraid to do — seek the justice we are forbidden. They validate all those moments we felt like hitting the men back, the angry text rants about that one sexist male client, the frustration and confusion when we report a rape and it is ignored or the rapist is acquitted with nothing but a slap on the wrist.

Angry women in fiction are necessary because anger is human, and women are human — a fact that we have to fight daily to prove.

3. Because 'the angry woman’ was created by men

Lotta Rae is a historical fiction set in 1916 England, while Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl is of a psychological thriller and takes place in America nearly 90 years later. But one thing these two books have in common, besides a female behind the pen/keyboard that wrote them, is that they include male perspectives.

But why is this so? Why should we care about a man’s opinions in a story centred around the plight of a woman?

It’s because ‘female rage’ is not really female. What differentiates ‘normal’ rage from ‘female’ rage is precisely men’s experience of our anger. In Gone Girl, Nick Dunne seems to have an excuse for everything Amy is upset about. He despises his wife and constantly reiterates that she’s insane, and that he has no idea why she would do what she did.

Likewise, in Lotta Rae, William’s POV brings to the forefront the chasmic divide between the perspectives of the male assaulted and female victim. Lotta’s rage is rendered ‘female’ only by comparison with William’s — because men have already set the rules for what ‘anger’ is supposed to look like, and what is okay to be angry about and what isn’t.

At the end of the day, we’re just girls living in a boy’s world. We play by their rules, do the exact same things they do. We eat, shit, sleep, bleed like them. And yet, everything we do is still defined by their standards — their existence is the yardstick against which we measure ours. And thus, we have ‘feminine’ rage.

TL;DR: Just cut us a break, man

All this is not to say that feminine rage should not be. The patriarchy has made it necessary to gender rage. In response, women have learned to weaponise our anger instead of swallowing it — and sometimes that is okay. After all, it is the strongest driving force behind social and political movements aimed at achieving gender equality and challenging gender-based discrimination.

From suffragettes to the #MeToo movement, our anger has empowered women to speak out, demand justice and equality, and fight against the societal norms and power structures that do not provide us the same allowances they do men. Of course, I’d be remiss not to acknowledge the men who are on our side and use their privilege to fight alongside us as allies. But while their numbers are many, it is not quite enough. Yet.

The light at the end of the tunnel for gender-based discrimination and oppression is just a pinprick in the distance, but feminine rage in literature and other forms of artistic expression remains a powerful tool for challenging these injustices in the ways we know how. The character of Medusa has become a popular tattoo amongst women who have been sexually assaulted, and there has been an uptick of BookTube/Booktok videos dedicated specifically to books about female rage.

These things are little, but play a great part in reminding women that it is okay to feel angry and hurt, and, more importantly, that we have the right to vocalise it. We have the right to push back. We have the right to take up space.

Feminine rage is necessary because all women — angry or not — are necessary, and we will do well to remember that.

Read my thoughts on the Roald Dahl censorship 👉 Roald Dahl On Trial

Rosamund Pike slitting NPH's throat made me choke in real life. 🥴